I sent this text to about a 100 random women in my phone book before I wrote this piece. Most of these women are urban, educated and seemingly liberal. Only 4 of them replied, surprisingly only those whose families were not silent about periods; however, despite their awareness and understanding, menstrual taboos had applied ‘minimal’ restrictions upon them such as not entering sacred spaces.

The silence and shame associated with talking about this issue, to even a fellow woman, is quite evident. Such taboos are passed on from one generation of women to another conveniently because women/girls are socialized into a state of ‘learned helplessness’ as suggested by Lenore Walker, though in the context of domestic violence victims/survivors, where the victims/survivors begin to think of themselves, their anatomy and their sexuality as subordinate to others, and dirty.

The conversation about periods began much earlier for most rural girls in my home state in Himachal Pradesh than it does for most of our little girls in cities today. Little girls there know that every few days women in their homes and families are secluded because they are ‘dirty’ and must remain separated from the rest of the family during that time.

Menstruation, in some local Pahari dialects is referred to as “Zudke” which literally means ‘clothes’ and so it is not even referred to as anything related to the female anatomy, but to the clothes or rags the women traditionally use to soak their flow in. Even the popular Hindi words such as Maasik, Maheena, and Mahavaari refer to a monthly occurrence, indicating no connection directly to the female body.

Little girls by default in hilly villages become the carriers of food and messages to and fro between the ‘Obra’/’Khudh’ (cow/cattle shed) and the house even as their mothers, aunts, female cousins and older sisters are confined/secluded during their ‘unclean’ period. These practices are believed and enforced with deep cultural conditioning suggesting that contamination from menstruating women can bring the worst curses from local deities upon people and even lead to the drying up of crops or the spread of secret diseases.

These girls thus grow up thinking of their own bodily functions as curses and impurities. This culture in hand with ‘god men’ and local deities, pressurizes women to adhere silently to this seclusion and humiliation month after month. It is also important to understand the generic architecture of homes in the hills to realize how traumatic and humiliating this seclusion can be for most women, especially young girls.

Traditionally the homes were made up of wooden structures with two floors, while the upper floor were the family quarters, the ground floor roomed the cattle and the sheep and so women were confined there during their menstrual phases. With changing times, cattle sheds are now constructed as a single hut slightly away from the main house and the seclusion thus becomes even more evident and in some cases unsafe too. The door is locked from outside and in case of an emergency like a fire, even the loudest cries may not reach the house. Toilets if there are any, are also constructed closer to the main house and women are often denied access to it during this time.

Social and economic upward mobility and some work by social initiatives and NGOs have probably increased awareness about menstrual hygiene and girls are increasingly using modern sanitary products, but the discrimination at the ground level has not changed much. Women in some families might not be sent to cowsheds but even in their semi-urban or urban homes, they are confined to one room, have to sleep on the floor, can’t go to the kitchen or prayer room, can’t touch some eatables like pickles and can’t touch other family members and so on and so forth.

While women slog equally in fields and kitchens all year round, only men participate in most religious rituals in villages and cook the sacred feasts and only they are allowed to offer yields to the deities. Lots of rural girls drop out from school around their puberty due to a lack of support and awareness. Hundreds succumb to infections due to unhygienic methods of managing menstruation.

The religious notions of purity and pollution are rules that deny women the basic human rights of caring about their health and bodies. All women, regardless of their caste are considered unclean during menstruation. Sometimes they are not allowed to even bathe, especially for the first few days of their menstrual period as it is believed that they can contaminate the water sources permanently.

The argument often propounded in favour of seclusion is that the confinement frees a woman of all her household duties during those days and she can take rest. Even if a rational benefit of doubt is granted to that logic, what kind of rest does a woman experience if she is psychologically stressed by separating her from her children and family and when the physical comforts of her kitchen and bedroom are denied to her?

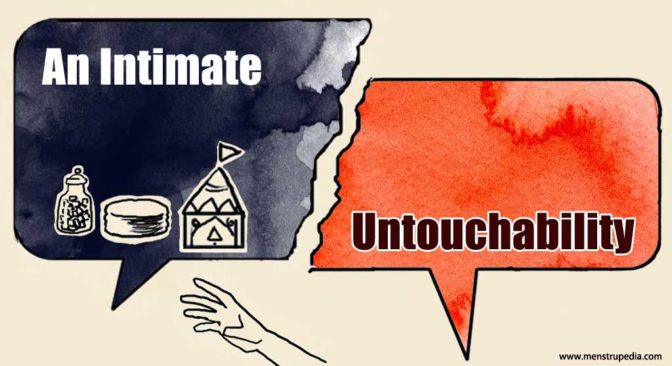

Untouchability based on caste and religion was ended legally long ago by our constitution, but this untouchability of a more personal and intimate kind is still practiced in many homes and families, and the worst part is that it is taken for granted too, both by the perpetrators and the victims.

There is no open discourse about it within families; TV channels still get changed whenever there is a sanitary napkin advertisement playing, and women though are not tied with physical ropes to restrain their movements and daily routines, still have stronger but invisible ties binding them securely to the margins, making them silently experience the shame and discrimination associated with menstruation.

Silence about menstrual taboos strengthens the shame surrounding it and the shame shrouding it strengthens the silence. Generations of women suffer in shame and in silence. It is time our girls are freed of this burden and can love their body and view their menstrual process as a privilege and not regard it instead, as a curse.

Author: Pooja Priyamvada

Pooja is a award wining writer/blogger. She is a voracious reader, tea connoisseur, loves to travel and has been deeply influenced by Sufi and Zen philosophy. Pooja writes regularly for online plateforms like Women’s Web, Feminism In India, Bonobology, Momspresso and The Mighty.

She blogs at: Second Thoughts First and पार्श्व स्वर

Editor: Divya Rosaline